The History of Pie

Posted by Warren

Vincenzo Cammpi, The Kitchen of pies, 1580s, oil on canvas

What is pie and what is not pie?

Where did the term Pie come from?

Invention of the flaky pastry.

Pie History from 1300 B.C. before Jesus.

Pie History around the World

The pies we know today are a recent addition to the history of food. However, the roots of pie go back as long as cooks had dough to bake with and a filling to stuff it with.

At one time everything baked in a oven was pie. The earliest ovens were actually large clay pots were fire was burned inside to heat them. Bread was baked in flat cakes on hot hearthstones. Clay in its wet form seem similar to dough. Meat was cooked directly exposed to fire on spits or over hot coals.

The problem of cooking meat this way is that the thing got burnt. The tasty juices dripped away and the meat was tough and dry. They got around this problem by wrapping the meat with leaves or mud to preserve the juices. Since dough seem like clay or wet mud, they wrapped the meat with dough made from flour and water to preserve the meat juices and prevent burning. This created the primitive juicy meat pie. Some medieval cooks called it a bake-mete.

The crust of this medieval pie formed like a baking dish. This serve for hundred of years as the only form of baking container for cooking over a fire or in a fire oven. Thus the meaning everything was baked in a pie.

The crust to these medieval pies served other functions. It acted as a carrying and storage container. By excluding air from its host, it help preserve the filling of meat or vegetables.

These medieval early pie crust were called coffins. It sounds bad today. It conveys the contents were dead. In fact the word originally meant a basket or box. This term was used first to describe a pastry casket of food before it came to refer to the funeral session.

The crust of these medieval pies or coffins were several inches thick to withstand many hours of cooking. They were very hard and inedible to eat. Only its content was eaten. If these coffins of dough were eaten, it done by the hungry beggers, the desperately poor or the scullery boys at the gates of the wealthy.

This thick crust was sometimes reused to thicken boiled stew. It was used like we use a roux as a thickener.

During the Medieval times of England, they were called pyes. Instead of being a sweet dessert they were mostly filled with meat like beef, lamb, wild duck, magpie pigeon and with spices of pepper, currants or dates.

Historians like to trace the meat pie’s origins to the Greeks. The Romans, on the other hand like their pies sweet. Meat pies were also part of Roman dessert courses but had a sweet version called secundae mensea.

Contrary to grade school teaching of Thanksgiving, the first celebration in 1621 did not feature pumpkin or pecan pie. The Pilgrims who colonized America brought British forms of their pies of meat-based recipes with them. Pumpkin pie, was first recorded in a English cookbook of 1675. It originated from British spiced and boiled squash. It was not popular in America until the early 1800s.

The colonists did cook many pies since it served to preserve foods that filled them. These fillings would keep fresh during the winter months. Pilgrims used dried and fresh fruit, cinnamon, pepper and nutmeg to season their meats. As the colonies spread out to other territories in America, the pie’s role as a means to showcase local ingredients took hold. There came to be a proliferation of new sweet pies.

A cookbook from 1796 may list just a couple of sweet pies. A cookbook written of the late 1800s may feature many recipes of sweet pie. By 1947 a Modern Encyclopedia of Cooking listed over 60 varieties of sweet pies.

The saying that “as American as apple pie” is not totally absolute. Like many traditions, the apple pie originally came from England. Before the Revolutionary, these apple pies were made with unsweetened apples and surrounded by an inedible pie crust or shell. Still the apple pie did develop a liking, and was first referenced in the year 1589, in Menaphon by poet R. Greene:

“Thy breath is like the steeme of apple pies.”

Pie started to become a lost art in America by the 1970s. Nevertheless, today pies are spanning the world as a favorite treat and are becoming more popular. The American Pie Counsel goal is to keep the pie alive. One way they accomplish this today is by hosting pie contests like the Crisco National Pie Championship which feature different competitions for the classic apple, pumpkin and cherry pie divisions.

Pies have come a long way to reach our dining tables today. Many bakeries are adding new varieties every day. The Little Pie Shop in New York City says the classic apple pie is the top holiday seller. Pies are being requested and decorated for weddings. Watch out cake, here comes the pie.

What is pie and what is not pie?

Believe it or not a concise definition for pie does not exist that everyone agrees with.

There are some pie definitions that some like while others would hate. Pies are not pies just because they are called pies. The American treat called Eskimo pie is definitely ice cream. Moon pie is a chocolate biscuit. Boston cream pie is certainly a cake baked in a pie tin.

How do we handle a cobbler or pandowdy? As failed pies with creative tops. Then we have cottage pie and shepherd’s pie. But none of these pies have a pastry.

First Law of Pies: Pies must have a pastry made from some sort of grain, wheat, rice, cracker or cookie crumbs. No pastry, No pie!

Second Law of Pies: Pies must be baked in an oven at some time of the process or pseudo bake – like no baked pie custards. Pies are not fried, boiled or steamed.

What? Not fried! This comes to our next pie law. We must quantify the time period we are defining pie for since it took on different means through the ages. Pies from the 16th century until now where all baked in a dish, a pie dish, and of an edible tasty crust. So the definition of pies will cover the time period of the 16th Century until now.

Therefore, our pie definition will not include fried pies that are more like turnovers or store bought package pies like Hostess. A fried pie is really no different than a jelly filled doughnut.

Fried pastry is not what we visualize when we thank of pie. If so? Why not call a fry won ton a pie.

Third Law of Pies: A pie shall be baked in some form of a dish – metal, ceramic or glass.

The next point to make is which pastry is mandatory or how many? Must it have a bottom crust or must it have a bottom and top crust. Maybe you prefer just a top crust.

Oxford English Dictionary defines a pie as:

A baked dish of fruit, meat, fish, or vegetables, covered with pastry (or a similar substance) and freq. Also having a base and sides of pastry. Also (chiefly N. Amer.): a baked open pastry case filled with fruit: a tart or flan.

It seems Europe makes the top crust essential to be a pie.

America makes the bottom crust the primary statue for a pie.

According to the British English bakers, the American open single crust pie is a tart or flan. So the definition is less clear. For argument state if you are in America, a pie must have a bottom crust of some sort of pastry.

Fourth Law of Pie: A pie in America must have a bottom crust of some sort of pastry.

Is a tart, a pie and a pie a tart? Tart comes from the word torture, which comes from the same Latin root. The pastry is twisted or torture to fit the dish which is layered with custard and jam, decorated with fruit, leaving it in all other respects ‘open’, just a bottom crust.

A tart never has a top crust. The filling of tarts are not as deep as a pie and tend to be somewhat shallow. Not mandatory but tarts have optional sides of pastry, and if there is one, the sides are in most cases perpendicular to the base.

Common tarts have a custard base stuffed with fruit laid out in an organized matter.

Tarte Tatin is an upside down tart, normally filled with fruit like apples.

Fifth Law of Pie: A pie must have a pastry that comes up on the sides to contain its filling. A tart is a subset of the pie. If sides are perpendicular, filled with custard and topped with fruit, the pie is called a tart.

Where did the term Pie come from?

Really, no one knows. The best source comes from the Oxford English Dictionary:

The origin for the word pie is uncertain and that no further related word is known outside English. It suggests that the word is identical in form to the same word meaning ‘magpie’ which is held by many to have been in some way derived from the connected word. The connection is that is that a pie has contents of have natural fillings like fruit and vegetables, similar to the magpie colorful odds and ends picked to adorn its nest.

Supporting the magpie idea – Without its filling a pie resembles a bird’s nest, circular in form, a flat bottom with raised sides. A structure designed to hold its content securely as a bowl.

A French connection can be made with the pie word. The English language was different after the Normans invaded in 1066 and a whole lot of pie-words appear in French and English to suggest similar meanings – like the tart and tourte.

The French word pate comes from the same root as pastry which is from various themes of flour and water. The pie, a pastry wrapped food got its name from this.

Invention of the Pastry:

Dough becomes a pastry when fat is added. Not any old dough or fat of random mixing.

The task of a pastry is to get just the right amount of gluten to make the pastry light and flaky. The pastry could only originate where wheat was grown. The other ingredient needed is fat. Not all fat is created equal. The ideal fat for a pastry has a high melting point and very little water content. Even though butter is a fat, its melting point was too low and viewed has a poor mans fat – butter was used later on. Today we can use it because of refrigeration. Lard was the fat to use. Therefore, this means pigs or cows were also accessible in the area where pastries were born.

As for the time frame when the pastry was invented, we know wheat and lard came together. We can figure that the pie began its life before the fourteenth century in Europe where wheat was grown and pigs and cattle were raised. This form of pastry spread to the Italians of the Renaissance, France, Britain and the rest of Europe.

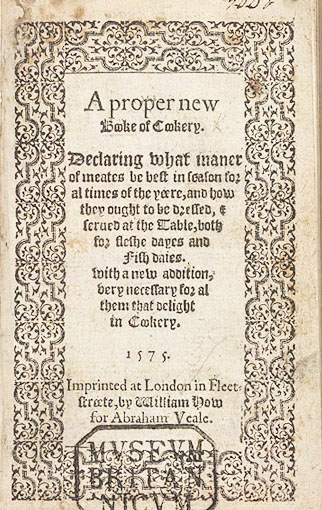

Recipes for pastry dough started to appear in cookbooks in Europe in the 16th century.

A Peopre New Booke of Cokery, published in London in 1545:

-To make a short paest for tarte –

Take fyne floure and a cursey of fayre water and a dyshe of swete butter and a lyttel saffron, and the yolckes of two eggs and make it thyne and tender as ye maye.

The instructions for these early cookbooks lack detail. They depended on much assumed knowledge and were intended more as an aid for experienced cooks. Clearly, by the 16th century short, puff and choux pastries were established.

An important historical fact of the pie is that it is a self contained meal, which can be eaten with hands without a dish. This convenient feature of the pie marked its success in England. Pies pre-date the sandwich of similar use but not in form.

The philosophical era of the Renaissance encourage the development of all the arts and wealthy families. These had money for indulging in there desires of all the good things in life. This funded the brilliant and imaginative bakers to use culinary ideas and techniques with pies.

Pie History from 1300 to 1200 B. C.

The bakers to the pharaohs, a king who believes he is god, incorporated nuts, honey, and fruits in bread dough, a primitive form of a galettes. Drawings were found on the tomb walls of Ramses II, located in the Valley of the Kings. King Ramses ruled from 1304 to 1237 B.C. Ramses III of 1186 to 1155 B.C. also used galettes of spiral shapes on tomb walls.

The tradition of galettes, the beginnings of pie, was carried on by the Greeks. These pies were made of a flour and water paste wrapped around meat. This served to cook the meat and seal in the juices.

Pie History Roman times – 234 to 149 B.C.

When the Romans defeated Greece, they brought with them Greek culinary foods like the galettes. The wealthy and educated Romans used many types of meat in every course of the meal, including dessert course (secundae mensea). The secunda mensa was a sweet course or dessert, consisting of fruit or sweet pastries.

Cato the Younger (234-149 B.C.), a politician and statesman in the late Roman Republic, recorded the popularity of this sweet course, and a cheesecake like dish called Placenta, in his treatise De Agricultura, a Latin writing of small farms in Italy. Placenta was more like a cheesecake pie, baked on a pastry base, or sometimes inside a pastry case.

The delights of the pie passed from Egypt to classical Greece and then to Rome and the rest of Europe. The pie was adapted to their customs and food availability as it migrated across the lands.

Pie History – 13th Century

A Tortoise or Mullet Pie was in a Thirteenth Century cookbook called An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook:

Tortoise or Mullet Pie – Simmer the tortoises lightly in water with salt, then remove from the water and take a little murri, pepper, cinnamon, a little oil, onion juice, cilantro and a little saffron; beat it all with eggs and arrange the tortoises and the mullets in the pie and throw over it the filling. The pastry for the pie should be kneaded strongly, and kneaded with some pepper and oil, and greased, when it is done, with the eggs and saffron.

Apple pie has been around in Europe since the Middle Ages. Medieval and Renaissance recipes for apple pies or tarts have shown up, in one form or another, in English, French, Italian and German.

Pie History in 14th Century

During Charles V (1364-1380), King of France, reign, gave lavish banquets of food dishes and acts of minstrels, magicians, jugglers, and dancers. The pie was used to produce elaborate “soteltie” or “subtilty.” Sotelties were food disguised in an ornamental way (sculptures made from edible ingredients but not always intended to be eaten).

A fourteenth century apple pie

From The Forme of Cury: XXVII For to make Tartys in Applis.

Tak gode Applys and gode Spycis and Figys and reysons and Perys and wan they are wel ybrayed colourd with Safron wel and do yt in a cofyn and yt forth to bake wel.

In the 14th to 17th centuries, the sotelty was not always a food, but any kind of entertainment to include minstrels, troubadours, acrobats, dancers and other performers. The sotelty was used to alleviate the boredom of waiting for the next course to appear and to entertain the guest. If possible, the sotelty was supposed to make the guests gasp with delight and to be amazed at the ingenuity of the sotelty maker.

The chefs entered into the fun by producing elaborate “soteltie” or “subtilty.” Sotelties were food disguised in an ornamental way (sculptures made from edible ingredients but not always intended to be eaten or even safe to eat. The sotelty was used to alleviate the boredom of waiting for the next course to appear and to entertain the guest. The sotelty was to surprise the guests with delight and to be amazed of the imaginative sotelty maker.

A Bake Mete of the 15th Century of England.

Take an make fayre lytel cofyns; than take Perys, & yif they ben lytelle, put .iij in a cofynne, & pare clene, & be-twyn euery pere, ley a gobet of Marow; & yf thou haue no lytel Perys, (some creative spelling) take grete, & gobet hem, & so put hem in the ovyn a whyle; than take thin commade lyke as thou takyst to Dowcetys, & pore ther-on; but lat the Marow & the Perys ben sene; & whan it is y-now, serue forth.

History of pies in the 16th Century

1520 to 1530s. At one banquet during the reign of King Charles V, a chef of the Duke of Burgundy created a huge pye with a captive girl inside! Musicians, also inside, played a tune when the pastry was opened.

Surprised pies (pyes) were popular at banquets for entertainment. The nursery rhyme “Sing a Song of Sixpence – four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie,” is one such pie. The rhyme says, “When the pie was opened, the birds began to sing. Wasn’t that a dainty dish to set before the King.” When to birds flew out singing the guest were amazed.

But how were such pies made with live things in them like birds and people?

16th Century – In the English translated version of Epulario (The Italian Banquet), published in 1598, the following is written on making surprise pies:

To Make Pie That the Birds May Be Alive In them and Flie Out When It Is Cut Up – Make the coffin of a great pie or pastry, in the bottome thereof make a hole as big as your fist, or bigger if you will, let the sides of the coffin bee somwhat higher then ordinary pies, which done put it full of flower and bake it, and being baked, open the hole in the bottome, and take out the flower. (Notice how pies are described as coffins). Then having a pie of the bigness of the hole in the bottome of the coffin aforesaid, you shal put it into the coffin, withall put into the said coffin round about the aforesaid pie as many small live birds as the empty coffin will hold, besides the pie aforesaid. And this is to be at such time as you send the pie to the table, and set before the guests: where uncovering or cutting up the lid of the great pie, all the birds will flie out, which is to delight and pleasure shew to the company. (Live birds!) And because they shall not bee altogether mocked, you shall cut open the small pie, and in this sort you may make many others, the like you may do with a tart.

A sixteenth century apple pie 1545.

From A Propre new booke of Cokery: To make pies of grene apples.

Take your apples and pare them cleane and core theim as ye will a Quince then make your coffyne after this maner take a little faire water and halfe a disshe of butter and a little safron and set all this vpon a chafyngdisshe (no punctuation and poor spelling) till it be hote then temper your flower with this vpon a chafyngdissh till it be hote then temper your floure with this said licour and the white of two egges and also make your coffyn and ceason your apples with Sinamon ginger and suger inough. Then put them into your coffyn and laie halfe a disshe of butter aboue them and close your coffyn and so bake them.

Pie History in the 17th, 18th and 19th Century

British and American Pies in history:

The British were baking pies long before they colonized America. Pies were mostly savory topped with potatoes.

1620 – The Pilgrims brought their pie recipes with them. First they used berries and fruits that were local to the New World. They used round pans to cut corners and to stretch out their limited ingredients. The pans also tend to be shallow for the same reason.

1700s – Pies were served with almost every meal. These pioneer women stated to set the trend of pastry making and making it a form of American culture. Pie was a roughed dish that could handle the diverse temperatures of stoves using wood for heat. Soon pies took center stage at county fairs, picnics, and other social events.

Reverend George Acrelius published in Stockhold on 1796, A Description of the Present and Former State at the Swedish Congregations in New Sweden, here he describes the eating of apple pie all the year:

“Apple-pie was used all the year, the evening meal of children. House-pie, in country places is make of apples neither peeled nor freed from the cores, and its crust is not broken if an agon-wheel goes over it!”

1768 – Sweet Potatoe and Black slavery

One enslaved African told a free black in Charleston about the food eaten on the slave ship that brought him to America: “We had nothing to eat but yams, which were thrown amongst us at random–and of those we had scarcely enough to support life. More than a third of us died on the passage, and when we arrived at Charleston, I was not able to stand.”

The African yam, which is similar to the American “sweet potato,” remained a popular food among blacks and whites alike. To this day roasted and sugared yams and “sweet potato pie” are favourite southern delicacies–both having their origins in African slavery.

George Washington’s, the first President of the United States, favorite pie recipe was a pie of Sweetbreads, which are taken from Martha’s Historic Cookbook, a possession of the Pennsylvania Historical Society. Martha Washington (1731-1802) was a fine cook. The book features some of her dishes that were prepared in her colonial kitchen at Mount Vernon. Here one for the pie:

Pie of Sweetbreads – Drop a sweetbread into acidulated, salted boiling water and cook slowly for 20 minutes. Plunge into cold water. Drain and cut into cubes. Stew a pint of oysters until the edges curl. (sweetbreads are edible glands of an animal. Yuck!) Add two tablespoons of butter creamed with one tablespoon of flour, one cup cream and the yolks of three eggs well beaten. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Line a deep baking dish with puff paste (dough). Put in a layer of oysters, then a layer of sweetbreads until the dish is nearly full. Pour the sauce over all and put a crust on top. Bake until the paste is a delicate brown. This is one of the most delicate pies that can be made.

Mrs. Fisher, born a black slave, found her way to San Francisco soon after the Civil War. By dint of talent and hard work, she created a life and business there. She and her husband created a business manufacturing and selling “pickles, preserves, brandies, fruits, etc.”

Mrs. Fisher was proud of a Diploma awarded at the Sacramento State Fair in 1879 and two medals awarded at the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair, 1880, for best Pickles and Sauces and best assortment of Jellies and Preserves.

1879 – African Slave – Mrs. Fisher seems to have been supported by kind hearted citizens of San Francisco and Oakland who helped Mrs. Fisher to write and publish her Coconut Pie Recipe in 1881 as both she and her husband were illiterate.

Mrs. Fisher, born a black slave, found her way to San Francisco soon after the Civil War. By dint of talent and hard work, she created a life and business there. She and her husband created a business manufacturing and selling “pickles, preserves, brandies, fruits, etc.”

Mrs. Fisher was proud of a Diploma awarded at the Sacramento State Fair in 1879 and two medals awarded at the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair, 1880, for her baking and cooking.

1880-1910 – Samuel Clemens (1835-1910), also known as, Mark Twain, was a big fan of eating pies. His long time housekeeper and friend, Katy Leary, baked Huckleberry pie to get her master to eat lunch lunch.

According to The American Heritage Cookbook, Katy Leary said in her book on Mark Twain:

She ordered a pie every morning. She said, recalling a period in which Twain was depressed. “Then I’d get a quart of milk and put it on the ice, and have it all ready – the huckleberry pie and the cold milk – about one o’clock. He eat half the huckleberry pie, anyway, and drink all the milk.”

1900s – Legendary glutton and a ladies man, James Buchanan Brady (1856–1917), known as Diamond Jim Brady, loved pies of various types. A special dinner was arranged by architect Stanford White (1853-1906). A huge pie was wheeled in, a dancer emerged, naked, and walked the length of the banquet table, stopping at Brady’s seat and fell into his lap. As she fed the millionaire, more dancers appeared. Brady was well known to finish lunch with an array of several kinds of fruit pies.

Reference sources:

American Apple Pie by foodtimeline.org

African Crops and Slave Cuisine by slaveryinamerica.org

Oxford English Dictionary, Volume III, 1982.

Pie: A Global History, by Janet Clarkson.

The White House Cookbook by Mrs. F.L. Gillette in 1887 – Project Gutenberg